Naturalism

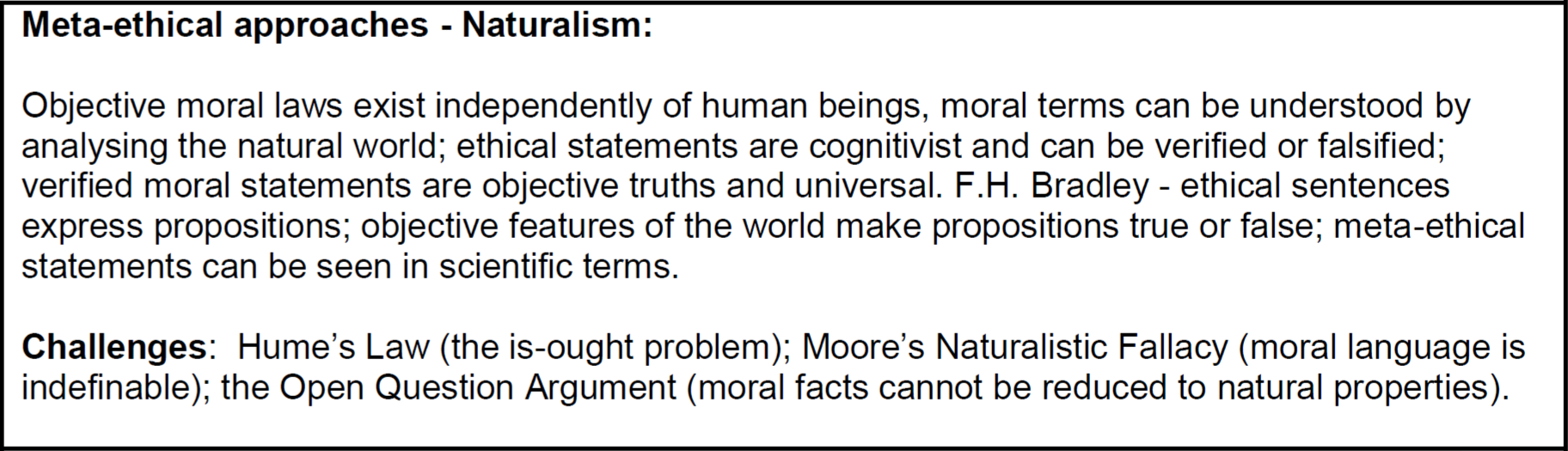

Meta-ethical approaches - Naturalism

Ethics involves discussing which actions are good. For example, is abortion ever morally good? There are many different answers to that question. Meta-ethics involves discussing what we mean when we say something is morally good. For example, when we say "Abortion is sometimes good", are we talking about a fact, a point of view, a feeling I have etc.? There are different answers to that question as well.

Naturalism answers the question, "What do we mean when we describe something as good?" by saying that good is a natural property of the world. So, sea water is salty, murder is wrong - these are objective facts (according to naturalism).

This links to work you will cover on Religious Language. Naturalism claims that moral truths are cognitive - they express facts about the world. Many ethical theories are Naturalist. For example, utilitarians disagree strongly with Natural Law about ethical issues - they say abortion may be right if it leads to the greater good. However, they agree with Natural Law that we can know the answer to moral questions. Utilitarians say that we know that pleasure is good and pain is bad because people desire pleasure and avoid pain. Natural Law says we can know that it is wrong to kill because we can see that all life strives to survive and reproduce.

FH Bradley

Bradley claimed that ethical statements are propositional. This means that an ethical statement expresses a claim that is either true or false. Bradley thinks that moral statements can be seen in scientific terms.

This is like two doctors disagreeing about treating someone - one doctor recommends meditation to reduce stress, while the other suggests medication. They disagree about what the right treatment is, but they both agree that we can work out which treatment is right by observation.

Is/Ought

Naturalism seems to be obviously right - utilitarians and Natural Law theorists can disagree about abortion, but there must be a right answer. Even if we can't know when it comes to abortion, surely we can know that it's wrong to murder or rape?

However, some people think that morality is very different from medicine. When it comes to meditation vs. medication, we can find out which works best by observation because we know what to look for. We can agree on a definition of physical health, so there is a right answer to questions like 'Does ibuprofen help reduce swelling?'. However, we can't agree on what 'good' means, so there is no right answer to the question. 'Is it good to allow two men to marry?' (or 'three men' or 'brother and sister' etc.).

Hume demonstrated this really clearly. Imagine two scientists talking about an experiment on a mouse. The spine is broken, and they make a cloned embryo of the mouse and use this to regrow the spinal column. They might check whether this worked by looking at the degree of movement the mouse has afterwards, whether it can swim or walk or run etc. However, if someone asks the scientists 'Was it morally wrong to break the spine of the mouse to learn these things?' they have moved away from science. The scientists can't say 'We'll just check,' because there is no way for them to observe whether we ought morally to experiment on mice.

Hume says this: "In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence."

What he means is that people talk about what is and what is not, and suddenly start talking about what ought to be, and that this is an entirely different sort of thing. Most importantly, we are on sound footing talking about what is, as we can see what is or is not, but we cannot observe what ought to be.

A really good example of someone making this error is Sam Harris. Harris is one of the New Atheists. He has a PhD in cognitive neuroscience, but did a degree in Philosophy, and has written about how science can determine human values. Harris uses the example of smacking children - we now know it is wrong to physically reprimand children because we can study the physical and psychological effects of corporal punishment.

Harris seems to be right, but the mistake he makes is an important one. Harris shows that smacking children stops them flourishing as people. We could argue about his data on this, but if it makes it easier, imagine we were talking about putting cigarettes out on children. We'd all agree that this stops a child from developing healthily and becoming a happy adult. However, the problem comes when we dig down and ask why it is wrong. We could say 'It is wrong because it causes harm to someone, and it's wrong to cause harm to someone.' Of course it is wrong, but we can't observe that scientifically. We could say to scientists 'We don't want to do anything that causes harm to people,' and then scientists could work out what causes harm to people and we can call that wrong. However, we have to decide whether it is wrong to cause harm to people.

Let's go back to the mice. I could say to a scientist, 'We don't want to do anything that causes harm to a mouse.' Scientists could then work out which procedures were wrong, according to our value judgment. We have to make the value judgment, though. The scientists couldn't work out if it was morally wrong to harm a mouse.

The Naturalistic Fallacy

GE Moore put it another way. Moore would agree with Harris about smacking children - Moore was a utilitarian, and he would say it definitely is wrong to put cigarettes out on children. We all know that. However, Moore criticised classical utilitarianism that claimed pleasure is good, pain is bad. Hume would say you moved from 'is' (people can be seen to desire pleasure) to 'ought' (people should desire pleasure). Moore put it a different way.

Moore said you can't define good in natural terms. The reason for this is that we can ask 'Is pleasure good?' It usually is. In fact, we would struggle to think of examples when it isn't - maybe the pleasure we get watching fail videos on Youtube might actually be bad, but generally pleasure is good. Moore said it is still an open question, so they can't mean the same thing. Even if I think about it and every example of pleasure is actually good, I must mean something different by 'good' or I wouldn't have to think about it.

Moore called this the naturalistic fallacy. He said that you can't define good (a non-natural property) in natural terms. He compared it to colours. We all know what red is, but we can't define red. We just recognise it. In the same way, Moore said we know what is good and bad, but we can't equate goodness to a property of the world that scientists could study.